Antoine Horenbeek

GG – Could you tell us a little about yourself? How did your work in art begin?

Since I was a child, I have been interested in art. From the age of 5, I was already portraying my parents, drawing inspiration from the style of Picasso. I started out with drawing and painting, first learning on my own and then taking classes in art workshops until I was 18. Then I also did street art. I studied architecture, a field that is also completely linked to art. So I practiced a lot of different art forms. I have sometimes turned away from some. However, there is one who has always been with me and will follow me until the end of my life, photography.

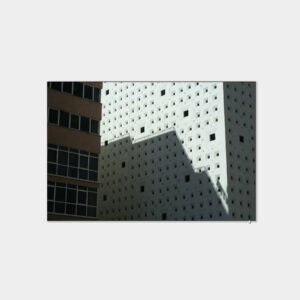

I am therefore an architect in addition to being a photographer. I have often regretted having studied architecture because I told myself that I should have followed my true vocation: photography. Then, little by little, I realized that I couldn’t “get rid” of architecture as easily as it was in me. After 5 years of study and almost as many years of professional experience, it is part of my vision of the world, of my culture. And that’s good because it also feeds my other artistic practices, just as my attraction to art feeds my architectural practice.

GG – We would like to know what do you think about your photography, what meanings, messages you put?

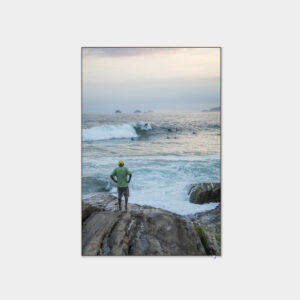

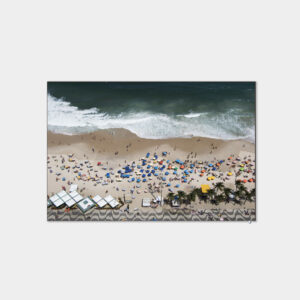

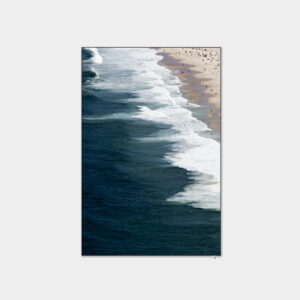

Thanks to this duality of architect-photographer, I work in a more interdisciplinary and unique way. My photographs deal with subjects related to architecture, town planning, social and urban issues, and right to the city. The projects I work on address the issue of slums and their lack of recognition as part of the so-called “formal” city (Intimate Favela, 2018), the intimacy and aesthetics of popular architecture (Mexico, 2019 ) or the relationship between public and private space and town planning in the cities of emerging countries (Brésil, l’aube, since 2015). My work is mostly documentary. It is political and aims to convey my vision of the world and share my commitment with others.

For me, documentary photography is not incompatible with conceptual and artistic photography, quite the contrary. My documentary photographs are sometimes thought out conceptually, but that doesn’t make them any less objective. This allows them precisely not to respond to sensationalism dictated by the media or to follow an editorial line. My images always have meaning. They refer to a representation of the world, to a certain reality, which I decide to put forward to tackle a deeper subject. This engaged form of photography, somewhere between art and documentary, is more accurate for me. This is an ideological and political gesture that does not lose its value as a document or information.

GG – What’s your earliest childhood memory?

I tried to remember when I was first interested in photography. It might have been born when I got a dual-eye view finder camera at the age of 6 (because I couldn’t close a single eye at that age). Or, if I go back further in time, this interest would originate during the amateur photoshoot organized by my father who took pictures of my mother while I was in her womb. The trigger may not really matter that much after all. Photography has always been in me and brings me closer to people. It allows me to get out of my body to interact with others.

GG – What could you imagine doing if you didn’t do what you do?

In another life, I would have liked to be a dancer. I find it to be one of the most interesting and complete artistic practices that exist because it mobilizes the entire physical body of the dancer but also his mind. I also like the simplicity of being able to make art using nothing other than yourself. There is nothing superfluous, it is disconcertingly simple and it gives a result of immense significance.

Artwork

Curriculum Vitae

Artist :

Antoine HorenbeekDate:

09/09/2021